Prediction-Oriented Algorithms

Contents

Prediction-Oriented Algorithms¶

In this lecture, we introduce supervised learning methods that induces data-driven interaction of the covariates. The interaction makes the covariates much more flexible to capture the subtle feature in the data. However, insufficient theoretical understanding is shed little light on these methods due to the complex nature, so they are often viewed by theorists as “black-boxes” methods. In real applications, when the machines are carefully tuned, they can achieve surprisingly superior performance. @gu2018empirical showcase a horse race of a myriad of methods, and the general message is that interaction helps with forecast in the financial market. In the meantime, industry insiders are pondering whether these methods are “alchemy” which fall short of scientific standard. Caution must be exercised when we apply these methods in empirical economic analysis.

Regression Tree and Bagging¶

We consider supervised learning setting in which we use \(x\) to predict \(y\). It can be done by traditional nonparametric methods such as kernel regression. Regression tree [@breiman1984classification] is an alternative to kernel regression. Regression tree recursively partitions the the space of the regressors. The algorithm is easy to describe: each time a covariate is split into two dummies, and the splitting criterion is aggressive reduction of the SSR. In the formulate of the SSR, the fitted value is computed as the average of \(y_i\)’s in a partition.

The tuning parameter is the depth of the tree, which is referred to the number of splits. Given a dataset \(d\) and the depth of the tree, the fitted regression tree \(\hat{r}(d)\) is completely determined by the data.

The problem of the regression tree is its instability. For data generated from the same data generating process (DGP), the covariate chosen to be split and the splitting point can vary widely and they heavily influence the path of the partition.

Bootstrap averaging, or bagging for short, was introduced to reduce the variance of the regression tree [@breiman1996bagging]. Bagging grows a regression tree for each bootstrap sample, and then do a simple average. Let \(d^{\star b}\) be the \(b\)-th bootstrap sample of the original data \(d\), and then the bagging estimator is defined as

Bagging is an example of the ensemble learning.

@inoue2008useful is an early application of bagging in time series forecast. @hirano2017forecasting provide a theoretical perspective on the risk reduction of bagging.

Random Forest¶

Random forest [@breiman2001random] shakes up the regressors by randomly sampling \(m\) out of the total \(p\) covarites before each split of a tree. The tuning parameters in random forest is the tree depth and \(m\). Due to the “de-correlation” in sampling the regressors, it in general performs better than bagging in prediction exercises.

Below is a very simple real data example of random forest using the Boston Housing data.

require(randomForest)

require(MASS) # Package which contains the Boston housing dataset

attach(Boston)

set.seed(101)

# training Sample with 300 observations

train <- sample(1:nrow(Boston), 300)

Boston.rf <- randomForest(medv ~ ., data = Boston, subset = train)

plot(Boston.rf)

importance(Boston.rf)

Despite the simplicity of the algorithm, the consistency of random forest is not proved until @scornet2015consistency, and inferential theory was first established by @wager2018estimation in the context of treatment effect estimation. @athey2019generalized generalizes CART to local maximum likelihood.

Example: Random forest for Survey of Professional Forecasters in data_example/SPF_RF.R from @cheng2020survey. The script uses caret framework.

Gradient Boosting¶

Bagging and random forest almost always use equal weight on each generated tree for the ensemble. Instead, tree boosting takes a distinctive scheme to determine the ensemble weights. It is a deterministic approach that does not resample the original data.

Use the original data \(d^0=(x_i,y_i)\) to grow a shallow tree \(\hat{r}^{0}(d^0)\). Save the prediction \(f^0_i = \alpha \cdot \hat{r}^0 (d^0, x_i)\) where \(\alpha\in [0,1]\) is a shrinkage tuning parameter. Save the residual \(e_i^{0} = y_i - f^0_i\). Set \(m=1\).

In the \(m\)-th iteration, use the data \(d^m = (x_i,e_i^{m-1})\) to grow a shallow tree \(\hat{r}^{m}(d^m)\). Save the prediction \(f^m_i = f^{m-1}_i + \alpha \cdot \hat{r}^m (d, x_i)\). Save the residual \(e_i^{m} = y_i - f^m_i\). Update \(m = m+1\).

Repeat Step 2 until \(m > M\).

In this boosting algorithm there are three tuning parameters: the tree depth, the shrinkage level \(\alpha\), and the number of iterations \(M\).

The algorithm can be sensitive to all the three tuning parameters.

When a model is tuned well, it often performs remarkably.

For example, the script Beijing_housing_gbm.R achieves much higher out-of-sample \(R^2\) than OLS, reported in @lin2020. This script implements boosting via the package gbm, which stands for “Gradient Boosting Machine.”

There are many variants of boosting algorithms. For example, \(L_2\)-boosting, componentwise boosting, and AdaBoosting, etc. Statisticians view boosting as a gradient descent algorithm to reduce the risk. The fitted tree in each iteration is the deepest descent direction, while the shrinkage tames the fitting to avoid proceeding too aggressively.

@shi2016econometric proposes a greedy algorithm in similar spirit to boosting for moment selection in GMM.

@phillips2019boosting uses \(L_2\)-boosting as a boosted version of the Hodrick-Prescott filter.

@shi2019forward

Neural Network¶

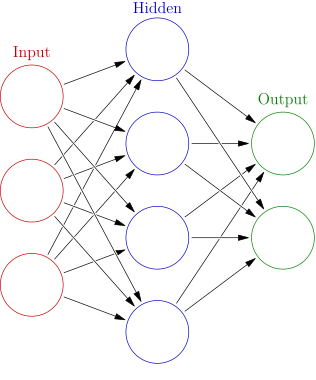

A neural network is the workhorse behind Alpha-Go and self-driven cars. However, from a statistician’s point of view it is just a particular type of nonlinear models. Figure 1 illustrates a one-layer neural network, but in general there can be several layers. The transition from layer \(k-1\) to layer \(k\) can be written as

where \(a_j^{(0)} = x_j\) is the input, \(z_l^{(k)}\) is the \(k\)-th hidden layer, and all the \(w\)s are coefficients to be estimated. The above formulation shows that \(z_l^{(k)}\) usually takes a linear form, while the activation function \(g(\cdot)\) can be an identity function or a simple nonlinear function. Popular choices of the activation function are sigmoid (\(1/(1+\exp(-x))\)) and rectified linear unit (ReLu, \(z\cdot 1\{x\geq 0\}\)), etc.

A user has several decisions to make when fitting a neural network:

besides the activation function,

the tuning parameters are the number of hidden layers and the number of nodes in each layer.

Many free parameters are generated from the multiple layer and multiple nodes,

and in estimation often regularization methods are employed to penalize

the \(l_1\) and/or \(l_2\) norms, which requires extra tuning parameters.

data_example/Keras_ANN.R gives an example of a neural network

with two hidden layers, each has 64 nodes, and the ReLu activation function.

Due to the nonlinear nature of the neural networks, theoretical understanding about its behavior is still scant. One of the early contributions came from econometrician: @hornik1989multilayer (Theorem 2.2) show that a single hidden layer neural network, given enough many nodes, is a universal approximator for any measurable function.

After setting up a neural network, the free parameters must be determined by numerical optimization. The nonlinear complex structure makes the optimization very challenging and the global optimizer is beyond guarantee. In particular, when the sample size is big, the de facto optimization algorithm is the stochastic gradient descent.

Thanks to computational

scientists, Google’s tensorflow is a popular backend of

neural network estimation, and keras is the deep learning modeling language.

Their relationship is similar to Mosek and CVXR.

Stochastic Gradient Descent¶

In optimization we update the \(D\)-dimensional parameter

where \(a_k \in \mathbb{R}\) is the step length and \(p_k\in \mathbb{R}^D\) is a vector of directions. Use a Talyor expansion,

If in each step we want the value of the criterion function \(f(x)\) to decrease, we need \(\nabla f(\beta_k) p_k \leq 0\). A simple choice is \(p_k =-\nabla f(\beta_k)\), which is called the deepest decent. Newton’s method corresponds to \(p_k =- (\nabla^2 f(\beta_k))^{-1} \nabla f(\beta_k)\), and BFGS uses a low-rank matrix to approximate \(\nabla^2 f(\beta_k)\). The linear search is a one-dimensional problem and it can be handled by either exact minimization or backtracking. Details of the descent method is referred to Chapter 9.2–9.5 of @boyd2004convex.

When the sample size is huge and the number of parameters is also big, the evaluation of the gradient can be prohibitively expensive. Stochastic gradient descent (SGD) uses a small batch of the sample to evaluate the gradient in each iteration. It can significantly save computational time. It is the de facto optimization procedure in complex optimization problems such as training a neural network.

However, SGD involves tuning parameters (say, the batch size and the learning rate. Learning rate replaces the step length \(a_k\) and becomes a regularization parameter.) that can dramatically affect the outcome, in particular in nonlinear problems. Careful experiments must be carried out before serious implementation.

Below is an example of SGD in the PPMLE that we visited in the lecture of optimization, now with sample size 100,000 and

the number of parameters 100. SGD is usually much faster than nlopt.

The new functions are defined with the data explicitly as arguments. Because in SGD each time the log-likelihood function and the gradient are evaluated at a different subsample.

poisson.loglik <- function(b, y, X) {

b <- as.matrix(b)

lambda <- exp(X %*% b)

ell <- -mean(-lambda + y * log(lambda))

return(ell)

}

poisson.loglik.grad <- function(b, y, X) {

b <- as.matrix(b)

lambda <- as.vector(exp(X %*% b))

ell <- -colMeans(-lambda * X + y * X)

ell_eta <- ell

return(ell_eta)

}

##### generate the artificial data

set.seed(898)

nn <- 1e5

K <- 100

X <- cbind(1, matrix(runif(nn * (K - 1)), ncol = K - 1))

b0 <- rep(1, K) / K

y <- rpois(nn, exp(X %*% b0))

b.init <- runif(K)

b.init <- 2 * b.init / sum(b.init)

# and these tuning parameters are related to N and K

n <- length(y)

test_ind <- sample(1:n, round(0.2 * n))

y_test <- y[test_ind]

X_test <- X[test_ind, ]

y_train <- y[-test_ind ]

X_train <- X[-test_ind, ]

# optimization parameters

# sgd depends on

# * eta: the learning rate

# * epoch: the averaging small batch

# * the initial value

max_iter <- 5000

min_iter <- 20

eta <- 0.01

epoch <- round(100 * sqrt(K))

b_old <- b.init

pts0 <- Sys.time()

# the iteration of gradient

for (i in 1:max_iter) {

loglik_old <- poisson.loglik(b_old, y_train, X_train)

i_sample <- sample(1:length(y_train), epoch, replace = TRUE)

b_new <- b_old - eta * poisson.loglik.grad(b_old, y_train[i_sample], X_train[i_sample, ])

loglik_new <- poisson.loglik(b_new, y_test, X_test)

b_old <- b_new # update

criterion <- loglik_old - loglik_new

if (criterion < 0.0001 & i >= min_iter) break

}

cat("point estimate =", b_new, ", log_lik = ", loglik_new, "\n")

pts1 <- Sys.time() - pts0

print(pts1)

# optimx is too slow for this dataset.

# Nelder-Mead method is too slow for this dataset

# thus we only sgd with NLoptr

opts <- list("algorithm" = "NLOPT_LD_SLSQP", "xtol_rel" = 1.0e-7, maxeval = 5000)

pts0 <- Sys.time()

res_BFGS <- nloptr::nloptr(

x0 = b.init,

eval_f = poisson.loglik,

eval_grad_f = poisson.loglik.grad,

opts = opts,

y = y_train, X = X_train

)

pts1 <- Sys.time() - pts0

print(pts1)

b_hat_nlopt <- res_BFGS$solution

#### evaluation in the test sample

cat("log lik in test data by sgd = ", poisson.loglik(b_new, y = y_test, X_test), "\n")

cat("log lik in test data by nlopt = ", poisson.loglik(b_hat_nlopt, y = y_test, X_test), "\n")

cat("log lik in test data by true para. = ", poisson.loglik(b0, y = y_test, X_test), "\n")

Reading¶

Efron and Hastie: Chapter 8, 17 and 18.